Measuring Brain Activities

Introduction

Functional magnetic resonance imaging, or FMRI, is a technique for measuring brain activity. It works by detecting the changes in blood oxygenation and flow that occur in response to neural activity – when a brain area is more active it consumes more oxygen and to meet this increased demand blood flow increases to the active area. FMRI can be used to produce activation maps showing which parts of the brain are involved in a particular mental process.

Background

FMRI is one of the most recently developed forms of neuroimaging but the idea underpinning the technique - inferring brain activity by measuring changes in blood flow - is not new.

The development of FMRI in the 1990s, generally credited to Seiji Ogawa and Ken Kwong, is the latest in long line of innovations, including positron emission tomography (PET) and near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), which use blood flow and oxygen metabolism to infer brain activity. As a brain imaging technique FMRI has several significant advantages:

It is non-invasive and doesn’t involve radiation, making it safe for the subject.

It has excellent spatial and good temporal resolution.

It is easy for the experimenter to use.

The attractions of FMRI have made it a popular tool for imaging normal brain function – especially for psychologists. Over the last decade it has provided new insight to the investigation of how memories are formed, language, pain, learning and emotion to name but a few areas of research. FMRI is also being applied in clinical and commercial settings.

What does MRI measure?

The cylindrical tube of an MRI scanner houses a very powerful electro-magnet. A typical research scanner (such as the FMRIB Centre scanner) has a field strength of 3 teslas (T), about 50,000 times greater than the Earth’s field. The magnetic field inside the scanner affects the magnetic nuclei of atoms. Normally atomic nuclei are randomly oriented but under the influence of a magnetic field the nuclei become aligned with the direction of the field. The stronger the field the greater the degree of alignment. When pointing in the same direction, the tiny magnetic signals from individual nuclei add up coherently resulting in a signal that is large enough to measure. In FMRI it is the magnetic signal from hydrogen nuclei in water (H2O) that is detected.

The key to MRI is that the signal from hydrogen nuclei varies in strength depending on the surroundings. This provides a means of discriminating between grey matter, white matter and cerebral spinal fluid in structural images of the brain.

What does FMRI measure?

Oxygen is delivered to neurons by haemoglobin in capillary red blood cells. When neuronal activity increases there is an increased demand for oxygen and the local response is an increase in blood flow to regions of increased neural activity.

Haemoglobin is diamagnetic when oxygenated but paramagnetic when deoxygenated. This difference in magnetic properties leads to small differences in the MR signal of blood depending on the degree of oxygenation. Since blood oxygenation varies according to the levels of neural activity these differences can be used to detect brain activity. This form of MRI is known as blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) imaging.

One point to note is the direction of oxygenation change with increased activity. You might expect blood oxygenation to decrease with activation, but the reality is a little more complex. There is a momentary decrease in blood oxygenation immediately after neural activity increases, known as the “initial dip” in the haemodynamic response. This is followed by a period where the blood flow increases, not just to a level where oxygen demand is met, but overcompensating for the increased demand. This means the blood oxygenation actually increases following neural activation. The blood flow peaks after around 6 seconds and then falls back to baseline, often accompanied by a “post-stimulus undershoot”.

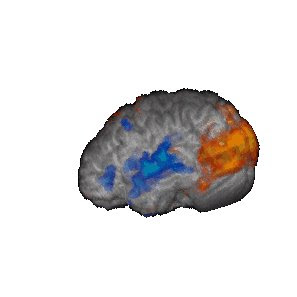

Activation Maps

The image shown is the result of the simplest kind of FMRI experiment. While lying in the MRI scanner the subject watched a screen which alternated between showing a visual stimulus and being dark every 30 second. Meanwhile the MRI scanner tracked the signal throughout the brain. In brain areas responding to the visual stimulus you would expect the signal to go up and down as the stimulus is turned on and off, albeit blurred slightly by the delay in the blood flow response. The ‘activity’ in a voxel is defined as how closely the time-course of the signal from that voxel matches the expected time-course. Voxels whose signal corresponds tightly are given a high activation score, voxels showing no correlation have a low score and voxels showing the opposite (deactivation) are given a negative score. These can then be translated into activation maps.

Source: University of Oxford, FMRIB,

http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/education/fmri/introduction-to-fmri/background/

<< Home